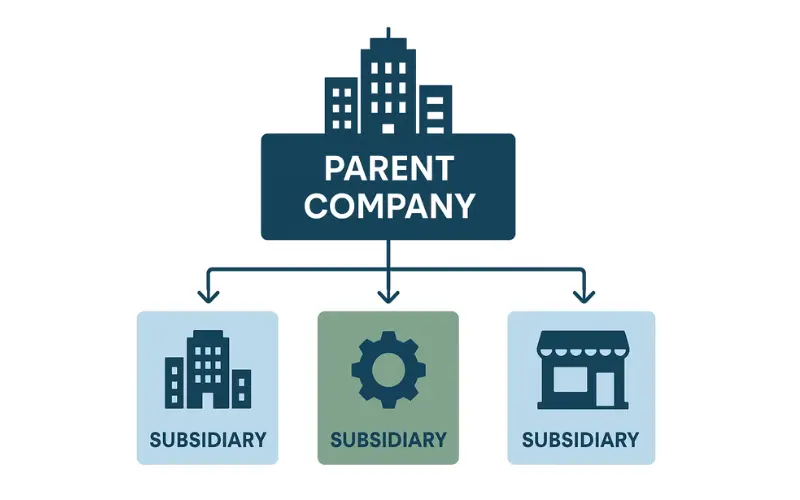

When most folks picture a company, they see one brand, one office, one leadership team. In practice, many businesses operate as a group of companies tied together by ownership and strategy. That’s where parent companies and subsidiaries show up. Nakase Law Firm Inc. often gets asked a familiar question from business owners: how does a subsidiary differ from a parent company in corporate structure? It sounds straightforward at first, yet the real story covers control, liability, money, and day-to-day decision-making across linked companies.

For starters, think of a business family. The parent sets direction and holds voting power; the subsidiaries carry out specific lines of work, each with its own legal identity. That framing helps when founders are also weighing basic formation choices. When folks are just getting set up, California Business Lawyer & Corporate Lawyer Inc. gets a companion question: what is a corporation, and how does it differ from an LLC? The structure you pick early on shapes how easy it is to add subsidiaries later, so these topics connect more than people expect.

What a Parent Company Really Does

Picture a growing apparel brand that wants to move into footwear. Rather than take every risk in the main company, the owners buy or form a separate company to run the shoe line. The original business becomes the parent; the new entity is the subsidiary. The parent owns enough voting shares to steer major decisions—board seats, executive hires, long-term strategy—without stepping into every small choice. Some parents are holding companies that mostly own other firms; others are operating companies with products of their own, plus a portfolio of subsidiaries.

How a Subsidiary Works Day to Day

A subsidiary is a separate legal person. It can sign contracts, own property, hire teams, and even end up in court under its own name. Ownership can be 100 percent, or shared with outside investors. That flexibility is handy. A software group, for example, might spin up a subsidiary to try a risky new product. If it takes off, great—the parent benefits. If it stalls, the loss generally stays contained in that one company. On top of that, a subsidiary can carry its own brand so the parent’s core customers aren’t confused.

The Legal Wall Between Them

Here’s the key legal idea: separation. A parent is usually treated as a shareholder of the subsidiary, not a guarantor of its debts. That corporate wall protects the parent’s assets if a subsidiary runs into trouble. That said, courts can tear down that wall if the parent treats the subsidiary like a mere facade—mixing bank accounts, ignoring formalities, or using it for dishonest conduct. In short, keep records clean, respect roles, and keep business dealings arm’s length.

How Money Moves in the Group

Money flows in a few familiar ways. A profitable subsidiary might send dividends up to the parent; the parent might push funds back down for growth. Investors in public markets often look at consolidated financial statements, where the parent reports results together with subsidiaries to give a fuller picture. Even so, each company maintains its own books. That balance—clear separation plus group reporting—helps owners keep risk in its lane and still show a unified view to stakeholders.

Who Calls the Shots

Leadership inside a subsidiary runs the business from day to day. The parent steps in on the big moments: strategy, executive selection, outsized capital commitments. If the subsidiary is wholly owned, the parent’s influence tends to be tighter. If minority investors hold shares, the dynamic shifts. Think of a coach and team: management runs plays on the field; the coach sets style, picks the lineup, and decides when to change course.

Why Build or Buy a Subsidiary

Real life provides plenty of reasons:

- Risk control for new products or markets

- Tax planning within legal boundaries across locations

- Local presence in new regions with different laws and customer habits

- Brand separation for different audiences

- Focused teams that can move without bumping into the parent’s existing operations

A quick example: a family-owned beverage company wants to sell an energy drink. A separate company lets them try bold flavors and edgy marketing without putting the parent’s main brand at risk. If it clicks, they can scale. If not, the setback stays contained.

Everyday Examples You See Often

Take Alphabet Inc. It owns Google plus several other companies focused on very different projects—from health research to self-driving tech. Each company can pursue its goals with room to breathe, yet the parent keeps a common direction. Another example is Berkshire Hathaway, which owns insurance firms, retailers, and utilities. Each company runs its own business, yet the parent handles capital allocation and overall game plan. These setups show how a group can spread risk across different lines of work.

Bumps in the Road

Nothing about this structure is effortless. Different regions have their own rules on employment, taxes, data, and reporting. Keeping each company compliant takes discipline and good advisors. There’s also the potential for friction with minority shareholders in a subsidiary. Picture a case where the parent wants to reinvest profits, yet a minority group wants cash dividends now. Clear agreements, thoughtful governance, and credible communication reduce that tension.

When a Parent Can Get Pulled In

Courts can hold a parent responsible if it starves a subsidiary of capital, treats it like an alter ego, or uses it to hide misconduct. Judges look for signs like shared bank accounts, no separate records, or a board that never meets. To stay safe, keep the basics tight: separate checks, proper minutes, fair contracts between group companies, and realistic funding for the subsidiary’s needs.

Growing Across Borders

Think about a U.S. brand moving into Japan. Running everything from the U.S. makes hiring, permits, and local marketing tough. A Japanese subsidiary can employ local staff, follow local rules, and tune products for local tastes. The parent still benefits from the new market, yet the legal risk and daily operations stay with the local company. Customers get familiar service; regulators get clean compliance; the group gets a thoughtful footprint in a new place.

Mini Stories from the Field

- A specialty coffee roaster created a separate company to sell tea. The tea team booked its own contracts with small farms and experimented with packaging that felt more premium. If a harvest failed or a product flopped, the coffee business stayed safe.

- A small software vendor bought a cybersecurity startup. Rather than absorb it on day one, the buyer kept it as a subsidiary so the new team could keep its culture and speed. Once the product lines meshed and processes stabilized, integrations happened piece by piece.

- A regional retailer tested a discounted outlet concept in a subsidiary. If shoppers loved it, they could scale across cities. If it didn’t resonate, they could close the unit without unsettling the main brand.

Common Questions That Tie This Together

People often ask: where does control end and independence begin? A useful check is this—can the subsidiary sign its own deals, keep its own books, and hold board meetings that actually matter? If yes, independence is real. Another frequent question: does the parent always roll up the numbers? For most groups with majority ownership, yes, because investors want the full picture. Yet lenders and partners may also ask for the subsidiary’s standalone results to assess risk at that specific level.

Bottom Line for Owners and Teams

So, how does a subsidiary differ from a parent company in corporate structure? The parent owns and guides; the subsidiary operates as its own legal company. The setup helps a group protect assets, test ideas, and reach new markets without placing every egg in the same basket. Get the basics right—separate records, clear governance, fair funding—and the structure becomes a steady platform for long-term plans.

That’s the practical view leaders use every day: pick the right base entity at formation, add subsidiaries with purpose, and keep the guardrails strong enough that each company can do its job without putting the rest of the group at risk.